Introduction

This article delves deeper into biomechanics, building upon insights from our previous two posts – using the shoulder joint, with its major and supporting muscles, as the example.

We will also delve into shoulder exercise dogma, common injuries and provide the optimal, joint safe exercises for shoulder muscle activation, strength and growth.

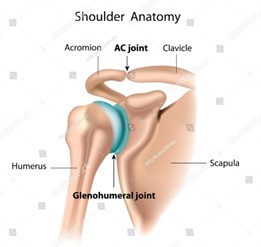

The Shoulder Joint

The shoulder, a marvel of human anatomy, plays a pivotal role in a myriad of daily activities and complex movements. Its intricate design and biomechanics warrant a thorough understanding, especially for those keen on optimizing their physical health and performance.

The shoulder joint, specifically the glenohumeral joint (where the head of the humerus fits into the socket of the scapula), is often considered to have the greatest range of motion of any joint in the human body. Its distinct ball-and-socket structure facilitates a broad range of movements across various planes:

- Flexion and Extension: Moving the arm forward and backward.

- Abduction and Adduction: Lifting the arm to the side and bringing it back down.

- Internal (Medial) and External (Lateral) Rotation: Rotating the arm inward and outward.

- Circumduction: A combination of the above movements, allowing the arm to move in a circular motion.

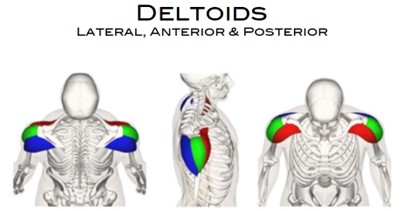

The Major Shoulder Muscles

As you can see in the image below, there are 3 major shoulder muscles – the front (anterior – coloured red), the side (lateral – coloured green), and the rear (posterior – coloured blue).

All 3 have the same insertion point on the upper arm bone (humerus), but each has a specific origin to enable the movements noted above.

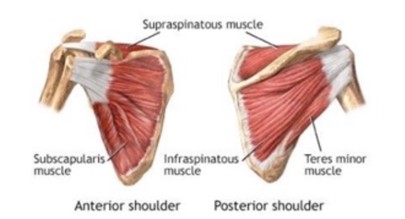

The Supporting Shoulder Muscles

The unsung heroes of the shoulders are the rotator cuff muscles, comprising of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis – see the image below.

The rotator cuff muscles are the guardians of our shoulder joint. They stabilize (help keep the shoulder joint intact), they rotate, and they are vulnerable to injuries, particularly with some ‘traditional’ exercises.

Shoulder Exercises

You will have learned in the previous post – Strength Training as we Age – that all muscles contract by pulling from their insertion toward their origin.

The optimal resistance exercise anatomical motion, for joint safety and to maximize muscle activation, is to follow this natural insertion to origin pulling direction.

Shoulder Exercise Dogma

The fitness industry appears to be recognizing the risks associated with certain shoulder exercises.

These include any behind the neck overhead press or behind the neck pull down and upright rows. However, you rarely see experts criticize the dumbbell or barbell front overhead press.

In fact, this front overhead press is touted as 1 of the ‘big 5’ and ‘must do’ heavy compound exercises. See also the ‘Myths’ Section in the ‘Strength Training as we Age’ post.

Our opinion at Age Free Strength, which is based on biomechanics, is that overhead presses of any kind are also prone to injury and are not optimal for target muscle activation.

Due to multiple contributing muscles, overhead Presses allow a heavier weight to be used, but do not load the deltoids any more than simple isolation focused exercises. The Overhead Press uses shorter levers (bent arms instead of straight arms), which reduces the magnification of the load to the Deltoids.

It also alters the alignment such that the origin and insertion of the deltoids are not on the same plane as the direction of resistance. It engages other muscles which assist (front deltoids and triceps) but are also not as productive for those assisting muscles, as other (better) exercises would be.

This is not to say you shouldn't lift anything over your head. We all need to on occasions and that's fine. However, regular heavy overhead pressing can cause a significant strain to the infraspinatus and increase the likelihood of developing shoulder impingement syndrome - as it did with me.

Biomechanics and Physics for Optimal Shoulder Exercises

Become a Member to see how these exercises fit into our Routines.

Watch this 2-minute video

Read the AD-Curve Free Post

By now, if you’ve followed this website, you will know that the optimal exercises we do, for joint safety and efficient / effective target muscle activation, do not require ‘lifting heavy’, or most of the traditional exercises, or typical gym equipment.

We adhere to principles from biomechanics, physics, and neurology to identify the most effective, efficient and safe exercises. These principles will have ‘yes’ answers to the following questions:

- Does it position the muscle better in terms of ‘opposite position loading’? (Physics).

- Does it improve the alignment? (Biomechanics).

- Is it a safe, natural joint movement? (Biomechanics).

- Does the resistance curve match the muscle strength curve? See the AD-Curve Post (Physics, Biomechanics and Muscle Physiology).

- Is it free of neurological interference? (Neurology).

- An example of neurological interference is ‘reciprocal innervation’, which in simple terms is the nervous system ‘switching off’ a muscle while its opposite muscle is working. Many compound exercises have this interference.

For those of you interested in delving into the science see the following courses in the Doug Brignole/Moe Larbi/SmartTraining 365 programs: The Brig20 Program and The Physics of Fitness.

The equipment we use is compact, lightweight and highly portable. Descriptions of this equipment can be found in the ‘Minimal Equipment for Maximum Results’ Section in the ‘Working Out While Touring and Camping‘ post.

So, with our Age Free Strength vehicle touring, camping, travelling and minimal home gym equipment journey – what are our optimal exercises for the 3 major shoulder muscles?

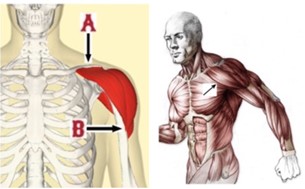

The Front (Anterior) Deltoids

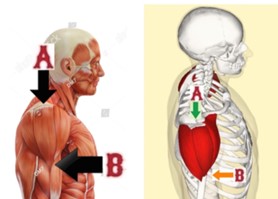

You can see from the image below that the front deltoid insertion (B) is on the upper portion of the humerus with its origin (A) on the outer half of the collar bone (clavicle).

The front deltoid participates in any movement where the humerus is pulled forward and/or upward – toward the collar bone (where the muscle originates). This includes all chest ‘pushing’ exercises. Remember that all muscles pull, none push – a pushing movement is the result of muscles pulling on bones (‘levers’ in physics terms).

These chest and other upper body pushing exercises involve the front deltoid, but not in the safest or the most productive way.

What movement works the front deltoid better (more efficiently and safely) than any other? Again – following our principles, we’ll seek the most natural way of doing that in as simple and straightforward a manner as possible.

The exercise demonstration below – the Front Deltoid Raise – is the optimal exercise for achieving the ideal range of motion, the early phase loading and it also provides opposite position loading (the front deltoid is positioned directly opposite the direction of resistance).

We were between camping trips when some of the videos were taken, staying with our son, daughter-in-law and grandsons in Darwin. It shows the versatility and portability of our minimal equipment (in these videos - the Unitree Pumps). We work-out the same, with the same equipment, when on the road, camping, or at homes.

All of these exercises can be done with the AD-Curve protocol or just with cables or resistance bands. While not providing the ideal resistance curve, bands do enable the ideal anatomical motion.

The optimal resistance curve is achieved when combining the Pump cables with bands in an AD-Curve setup.

Exercise Form Notes:

- Note the range of motion, there is no need to go too far back or too far forward – both of which can strain the shoulders.

- The first video is with the resistance anchored at shoulder width to minimize the chest pectoral engagement.

- The second video is with the resistance anchored wider with the intent to engage the upper pecs.

Side (Lateral) Deltoids

As per the image below, the side deltoid originates on the outer edge of the acromion process, on the collar bone (A). Its insertion is on the humerus (B) – adjacent to the front and rear deltoids insertions.

Notice that the direction of the fibers of side deltoids are parallel with the plane that runs through the origin and the insertion of the muscle. When it contracts (shortens), it brings the muscle insertion upward, toward the origin, thereby creating the movement known as ‘lateral abduction of the humerus’ – raising the arm sideways.

That motion is the ideal anatomical motion of the side deltoid. It represents the simplest, most natural function of the muscle, without any twisting or rotation of the humerus, nor any shoulder joint distortion.

The video below shows the optimal side deltoid exercise, the Lateral Raise, in action.

Exercise Form Notes:

- The pulley is set at the correct height – about where the hand is when hanging down. This provides the ideal resistance curve.

- Don’t lift higher than the shoulders as it will risk injury.

- Keep the shoulder ‘down’ – don’t shrug it up.

- Note the handle up and over my wrist. This takes the wrist and fingers, which would be the weak link, out of the exercise.

- I lift slightly forward to eliminate any shoulder pain (incurred through years of doing overhead presses).

Rear (Posterior) Deltoids

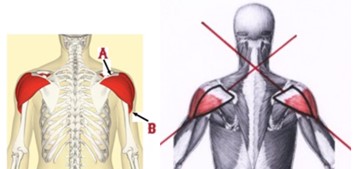

The image below shows the rear deltoids origin on the upper ridge of the shoulder blade/scapula (A), and the insertion on the humerus (B) adjacent to the other major shoulder muscles.

The primary function is to pull the upper arm back, and it also helps externally rotate it.

Our goal now is to identify the ideal direction of humeral movement that is produced by the rear deltoids, without bias – neither for nor against – traditional exercises. Again, we’ll use our principles of imagining the muscle insertion moving directly toward the muscle origin, in the simplest and most natural manner, and see what kind of movement that produces.

In the image above, red lines are drawn straight through the origin and the insertion of both (left and right) rear deltoids. With our principles stating that that there should be alignment between the direction of resistance, the direction of movement, and the origin / insertion of the target muscle, you will see that a ‘reverse V’ movement is optimal for the muscle activation – as per the demonstration below, the Rear Delts Pull-Away.

Exercise Form Notes:

- Start the movement with the hands no higher than the upper chest and pull down and away.

- There is no need to cross the hands over, starting them together is fine.

- There is no advantage or requirement to raise the arms horizontally (perpendicular with the torso) and ‘pull back’ as per many traditional rear deltoid exercises. In fact, doing that, can unnaturally strain and risk injury with the shoulders.

Become a Member to see how these shoulder muscle group exercises fit into our Routines.

Summary and Next Post

The shoulder, with its intricate design and biomechanics, plays a pivotal role in our daily activities and overall physical health. Understanding its structure and function is crucial for anyone keen on optimizing their physical performance and preventing injuries.

This article has shed light on the biomechanics of the shoulder, debunked some common exercise myths, and provided insights into safe and effective shoulder exercises. By adhering to the principles of biomechanics and physics, we can ensure that our shoulder workouts are not only effective but also safe.

We decided not to include a section on shoulder joint, muscle and ligament injuries, because if the above exercises are done correctly, injuries will be avoided. There is a plethora of online information on shoulder injuries – from impingement syndrome to bursitis to rotator cuff muscle tears and more.

I had a damaged right shoulder from years of doing overhead presses and barbell bench presses - but with these biomechanically optimal exercises performed with the Unitree Pumps and/or with resistance bands I can work-out without pain.

The Unitree Pumps are perfect for the optimal shoulder exercises. With their compactness, easy positioning options and more than enough resistance they are an ideal component of our travelling gym.

In conclusion, remember, it’s not about lifting the heaviest weights but about lifting the right way. Here’s to stronger, healthier shoulders!

Interested in Unitree Pumps? Click here for an additional 20% discountNot an Affiliate link

In our next exploration, we’ll delve deep into the world of abs and core exercises. Building on the insights from our previous three posts, expect to uncover some revelations that will challenge conventional wisdom.

From debunking myths to introducing innovative techniques, we promise a comprehensive guide that will reshape your understanding of abs and core training.

So, brace yourself (and your core) for some surprises. Stay with us on this journey to optimal fitness!